We reached out to PROFORMA’s coordinator, Professor Eleni Aklillu, to hear about the challenges and successes of building pharmacovigilance in the East African region.

Listen to the podcast

Professor Eleni Aklillu and Dr Abbie Barry (PROFORMA Project Manager) were the first external guests in Uppsala’s Monitoring Centre #DrugSafetyMatters podcast on ‘Advancing pharmacovigilance in Africa’. This in-depth episode explores among others specific pharmacovigilance challenges in the East African region and how to improve collaboration among public health programmes, academia and pharmacovigilance regulatory bodies.

Professor Aklillu, how did you become involved in pharmacovigilance?

Eleni Aklillu (EA): Over the past 20 years my research group has conducted several clinical pharmacology research projects on treating and preventing infectious diseases including HIV, tuberculosis, malaria, and various neglected tropical diseases (NTDs). This includes monitoring the safety and toxicity of treatment. Drug safety is a concern because treating these diseases often involves a combination of drugs, treatment duration is long, and coinfection and cotreatment increases the risk for drug-interaction and overlapping toxicities. Pharmacovigilance was therefore always a component of our research.

More recently though, I have focused specifically on strengthening pharmacovigilance capacity in Africa. Access to medical products and the number of clinical trials being conducted in the region have increased, but the regulatory capacity to monitor public medicine safety is limited. For example, the number of mass drug administration (MDA) and vaccination programmes to prevent and control various infectious diseases without prior diagnosis and safety follow-up has increased sharply. It is inevitable that some individuals may experience adverse events following immunisation or mass drug administration.

Identifying the type, incidence, and severity of adverse events as well as associated risk factors is important so that precautionary measures are taken. Recent studies including ours have indicated that comorbidity, co-medication including the use of traditional medicines, and genetic variations that are more common in Africa may increase the risk of adverse drug events. You may know that black Africans are the most genetically diverse population on earth. Thus, safety information generated through pharmacovigilance is critical to predict treatment outcome and prevent toxicity.

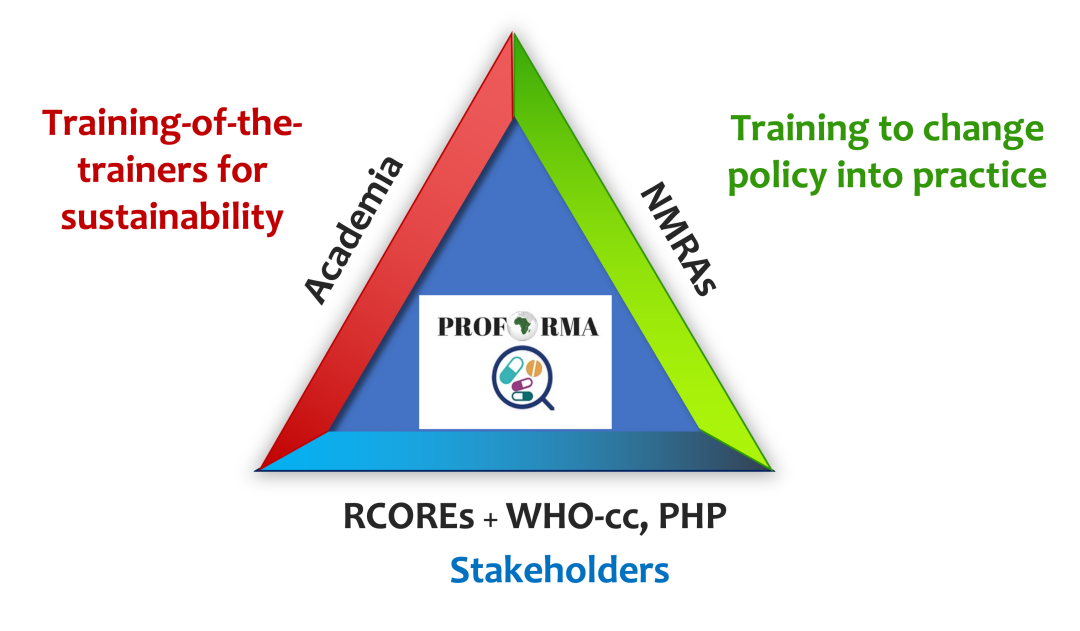

PROFORMA triangle model

Prof. Eleni Aklillu

At the start of the project, you conducted a baseline study to see how advanced East African countries’ pharmacovigilance capacities were. What differences and similarities did you find?

EA: We conducted a baseline comparative assessment of the national pharmacovigilance systems in Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, and Tanzania to identify each country’s strengths, gaps, needs and priorities for intervention. Our results found both similarities and differences between the countries. For instance, all four countries had a strategic plan, policies and legal frameworks defined by law and had regulation to conduct pharmacovigilance activities. However, the countries were at different levels of maturity to conduct pharmacovigilance activities, including the legal mandates to do so. Ethiopia, Kenya, and Tanzania had an established national food and drug authority, but at the start of our project Rwanda didn’t have such an independent authority. This indicated to us that country-specific targeted interventions were needed to strengthen the pharmacovigilance systems. Based on the findings from the baseline assessment, each of the four participating countries prepared a national pharmacovigilance roadmap with a short-, mid- and long-term implementation plan to strengthen the national pharmacovigilance system.

We also conducted a baseline comparative assessment of the pharmacovigilance systems within the NTDs and immunisation programmes. All four countries had strategic plans to integrate pharmacovigilance within their programmes. However, key elements were limited or missing such as the reporting of adverse events, a specific budget for pharmacovigilance, sustainable collaboration between the public health programmes and the national pharmacovigilance centers and other stakeholders including academia. For instance, despite millions of people receiving preventive chemotherapy through mass drug administration, no safety reports were submitted to National Medicines Regulatory Authorities (NMRAs) in 2017 and 2018. It is natural to have drug adverse events, and this should be recorded and analysed to identify signals, predict, and prevent treatment related harms.

Furthermore, we empowered local academic institutions by introducing an undergraduate and post-graduate curriculum. We developed an undergraduate pharmacovigilance curriculum for medical students, nursing, and pharmacy students which is now adopted by PROFORMA participating medical universities in East Africa. We also developed a post-graduate programme in pharmacovigilance and pharmaco-epidemiology which is accredited by the Tanzania Commission for Universities (TCU) and adopted by Muhimbili University for implantation. The first batch of MSc students have now been enrolled for training. We also developed an Edulink module for healthcare professionals, which will continue to exist after the project has finished. By creating these types of best practices, we are ensuring sustainability after the project ends.

Overall, I think the PROFORMA project has demonstrated how academia, regulatory authorities and public health programmes can jointly make robust safety assessments. In the past three years, many of them have achieved their goals, for instance through introducing electronic reporting systems or having critical acts and laws approved by their parliaments.

How are you tackling the collaboration and information exchange between the various stakeholders? What have been the best practices to date?

EA: We designed and implemented a PROFORMA triangle model to connect key pharmacovigilance stakeholders; the national regulatory authorities, academia, and the public health programmes. We established collaboration between the three key pharmacovigilance stakeholders and tested its functionality at different levels to support the implementation of the national pharmacovigilance roadmap. Using the PROFORMA triangle collaborative model we successfully demonstrated the feasibility of conducting large-scale active safety surveillance in MDA and vaccination programmes through effective collaboration between academia, national medicine regulators, and public health programmes in African settings. I am happy to say that the experience gained during our active safety surveillance of HPV vaccine in Ethiopia helped the Ethiopian authorities to do vaccine surveillance for COVID-19.

I believe that involving academia in medicine regulatory activities is critical for sustainable pharmacovigilance capacity strengthening. Projects are of limited duration, but pharmacovigilance is an ongoing process that needs to be fed with the latest insights to be sustained and innovate. Together with participants from Lareb, our university working group engaged in providing short-term training and workshops in pharmacovigilance. For the long-term training we adopted a trainers-of the trainers’ model. Currently 7 PhD students and 5 MSc students are being trained in pharmacovigilance under the PROFORMA project.

How do you think other regions can benefit from PROFORMA’s results and insights?

AE: We are seeing interest from other regions to get involved in the PROFORMA project. For me, the logical approach would be to focus on my own region that I am familiar with, but with follow-up funding we would be able to involve other regions in the future. Overall, the situation in East Africa may not be so different from for instance West Africa, and the model that we tested can be adopted by countries in other regions. Moreover, we are training MSc PhD candidates, who may serve the continent in any region or even at pan-African level and continue fulfilling the vison and mission of the PROFOMA project.

scroll down

“I believe that involving academia in medicine regulatory activities is critical for sustainable pharmacovigilance capacity strengthening. Projects are of limited duration, but pharmacovigilance is an ongoing process that needs to be fed with the latest insights to be sustained and innovate.”

— Professor Eleni Aklillu